Author: Leah Pattem

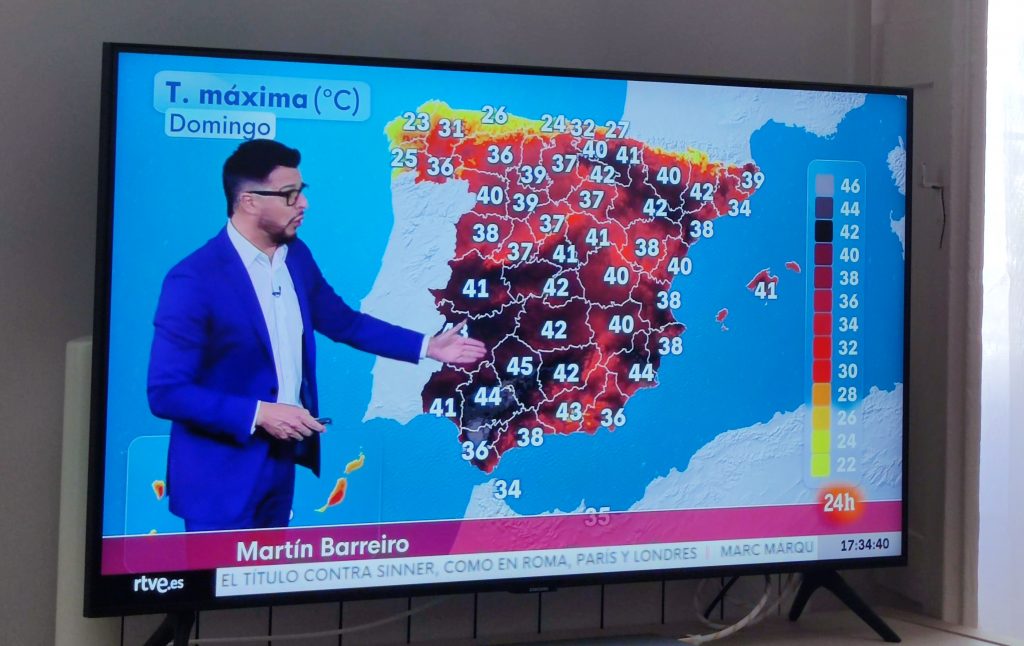

Spain was one of many European countries hit by record-breaking heat this summer. For three straight weeks in August, temperatures across the Iberian Peninsula soared past 40°C, with no relief after dark. Nights stayed above 26°C, a clear sign of the Urban Heat Island effect, where asphalt and concrete trap the day’s heat and release it slowly at night, preventing temperatures from naturally cooling off.

In Andalucía, temperatures hit even higher extremes, hovering around 45°C during the same heatwave. According to researchers from Imperial College London and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, this isn’t just bad luck, it’s deadly, and it’s human-made. Their early analysis of 854 European cities found that two in every three heat-related deaths this summer were caused by climate change.

From June to August, 16,500 out of 24,400 heat-related deaths in Europe were directly linked to rising greenhouse gases. The study found that climate breakdown made cities 2.2°C hotter on average, which is just enough to push thousands of more vulnerable citizens into overheating. Scientists claim that if we hadn’t spent decades burning fossil fuels, many of these people would still be alive. The scale of this crisis is starting to look like a heat pandemic, and yet it barely makes the headlines.

As usual, it’s older people who suffer the most: 85% of those who died were over 65, and nearly half were over 85. Most died in their homes or in hospitals, but heat is rarely listed on death certificates. But the truth is, the official data may still be underestimating the crisis, because the temperatures we’re shown on the news aren’t always the ones we actually feel.

Anyone living in Madrid knows this. We feel it in the burning pavements, the sauna-like metro stations and the sun-baked bus stops. And then suddenly, we step into Retiro Park and feel the drop, like a wall of cool, humid relief. The central park of Madrid also happens to be the location of one of the city’s three official temperature sensors is located, in the corner of the coolest, shadiest part of the city.

The reason for this is because weather models need an undisturbed reference point and Retiro gives them that. Inside Retiro, temperatures remain relatively unaffected by the city’s soaring UHI effect beyond its gates, but these readings also give the public – and the government – a false sense of security. While one part of Madrid may be at 38°C, another could be burning at 43°C, and there’s no official record of it. That’s where the Termometrada comes in.

Two summers ago, a group of local activists launched the citizen-led initiative called Termometrada to capture the real temperatures of Madrid. Using electronic thermometers, volunteers take readings at three times of the day: at sunrise, 5 p.m. during peak heat, and at midnight to measure overnight heat retention. Readings are taken in shaded areas, at head height and are logged once they stabilise.

In the last survey in 2023, over 150 people measured temperatures at 98 locations across 14 Madrid barrios. What they found were temperature differences of up to 15°C, depending on tree cover and urban layout. At sunrise, the hottest reading was taken in Plaza Lavapiés (31.5°C). The coolestn was in Pozuelo, one of Madrid’s wealthiest and greenest suburbs: just 16°C. By midday, Mercado de la Cebada was the hottest spot at 37.5°C, which is no surprise for a square that was controversially inaugurated without a single patch of greenery, despite plans for a vine canopy and flower beds, which have been left abandoned.

This year, Termometrada is going national. On Saturday, 20 September, nearly 700 volunteers will measure temperatures in 200 locations across more than 60 municipalities. This data will give us proof that what we feel isn’t in our heads, it’s in the air around us, and with that proof, we can demand action.

Because what we need now is urgent, targeted, structural change. We need more green spaces in every barrio, not just in privileged areas. Subsidised air conditioning in public spaces like schools, day centres, and care homes. A dense network of climate refuges across the city that are open, accessible, and well-publicised. More frequent public transport in summer, when service is often halved, leaving people to wait 15 to 20 minutes in scorching heat. For many, that wait is the most dangerous part of their day.

The climate crisis is already here, and cities like Madrid are on the frontlines. It’s time the official numbers caught up with what we already know: it’s hotter than they say it is, and it’s deadlier too.

Support this platform for just €1 per month

You may have noticed that I don’t run ads, nor accept sponsors or investors. Independence is everything and what I decide to publish will not be influenced by those in a position of capital, privilege or power. Therefore, I invite only you to support this platform and only you to help me keep doing what I do. Thank you, Leah.

Leave a Comment